#mondaymood: I like it DIRTY 🎟

- Laura Antoni

- May 25, 2020

- 5 min read

Hand sanitiser dispensers are everywhere these days — in schools, gyms, and offices of all kinds. Most parents feel compelled to carry a bottle of the stuff on their person or risk appearing irresponsible. Antibacterial substances are added to children’s toys and adult workout clothes. Yet, from my point of view as an immunologist and microbiologist, this growing fear of microorganisms is unnecessary and alarming. In fact, my research has led me to believe that what we need today isn’t less dirt — it’s more.

We live in an age of cleanliness. Our soaps are antibacterial. Our household cleaners promise to kill 99.9% of germs. Microbes are bad, plain and simple.

But at the same time, some scientists also tell us that being too clean is also wrong, because it might help cause asthma and allergies. It can disrupt our microflora and affect our gut health which can lead to thyroid problems, hormonal imbalances, weight gain and can have an impact on our mental wellbeing as well. So is there a balance between keeping obsessively clean and learning to live with the bacteria all around us?

The healthy human body harbours some 90 trillion microbes, outnumbering cells by about 10 to one. The majority of these organisms are beneficial; they compete with harmful microbes for space, aid in the function of the digestive system, and even produce factors to clot blood after an injury. Their presence keeps the immune system tuned and strong (a process I will explain later). Our societal obsession with destroying them is counterproductive to our well-being.

We have known since the late 19th Century – and the discoveries of German physician Robert Koch – that certain bacteria cause specific diseases. Since then, sanitation and cleanliness have dramatically improved our health.

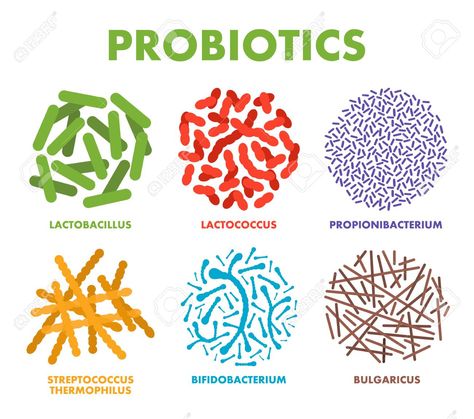

Yet not all microbes are bad. Yes, there are bacteria that cause unpleasant or even deadly diseases, but lots of them are extremely useful and beneficial to our health. They make vitamins in our gut, coat our skin to protect us from harmful microbes, and help us digest food. Outside of our bodies, they decompose organic waste, make half the world's oxygen and fix nitrogen levels in the air – helping make the Earth the life-supporting planet it is. Today, many scientists argue that people have become “too clean” for their own good.

"Knowing which sorts of microbes are normally found in healthy people can help us understand the roles that changes in microbe populations play in disease," says Dr. Curtis Huttenhower, associate professor of computational biology and bioinformatics in the Department of Biostatistics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Bacteria have gotten a bad reputation, and for good reason. Bacteria are behind a number of serious diseases — including pneumonia (Streptococcus pneumoniae), meningitis (Haemophilus influenzae), strep throat (Group A Streptococcus), food poisoning (Escherichia coli and Salmonella), and a variety of other infections.

These “bad” bacteria are the reason why we diligently disinfect our hands and wipe down our kitchen and bathroom sinks, as well as any other places where germs tend to congregate. We also have developed a wide range of antibiotics, which are drugs designed to kill the bacteria that cause disease.

Yet, not all bacteria are bad guys. In fact, our bodies are home to an estimated 100 trillion “good” bacteria, many of which reside in our gut. Not only do we live in harmony with these beneficial bacteria, but they are actually essential to our survival.

Good bacteria help our bodies digest food and absorb nutrients, and they produce several vitamins in the intestinal tract — including folic acid, niacin, and vitamins B6 and B12. According to research published in the journal Best Practice & Research Clinical GastroenterologyTrusted Source, beneficial bacteria may also protect us against their dangerous relatives that cause disease by crowding them out in the gut, producing acids that inhibit their growth, and stimulating the immune system to fight them off.

When helpful bacteria multiply and thrive in our bodies, they act as our protectors. But sometimes, we put the population of beneficial bacteria at risk. When we take antibiotics to treat an infection of harmful bacteria, we also kill helpful bacteria. This can cause an imbalance of bacteria in the body.

“We are getting far too sterile,” - Kiran Krishnan, a microbiologist and chief scientific officer for Microbiome Labs, based in St. Augustine, Florida. “Exposure to microbes is an essential part of being human. Most of our immune system is comprised of tissue that requires activation by the microbes we’re exposed to. The immune system requires the presence of friendly bacteria to regulate its functions. Think of the immune system as an army, with tanks and missiles but no general to lead them. That’s the role friendly microbes play in your body; they’re the general.” The vast majority of microbes, 97% to 99%, are benign or beneficial, and they are the best protection to fight pathogenic microorganisms, Krishnan says.

This doesn't go against good hygiene. Instead, they say that modern society has gone overboard with deploying antibacterial soap and germ-killing cleaning products, which indiscriminately kill germs – including good bacteria that help maintain a strong and diverse microbiome. Everyone has a microbiome, a collection of more than 100 trillion microbes that live on and in our body, the majority in our large intestine. “The more diverse your microbiome is, the healthier you are,” Krishnan says.

Diversity is the key to beneficial microbial populations. Not only does a wider array of microbes mean a greater variety of bacterial byproducts for body cells to use, it also leaves less territory for disease-causing bacteria to occupy. That's why the new approach to microbes is directed at maintaining a healthy balance of germs throughout the body.

Some of the best-documented benefits include assistance in the digestion of food components our guts can’t handle by themselves, regulation of our bodies’ metabolism, processing and detoxification of dangerous chemicals that we ingest with our food, training and regulation of the immune system, and prevention of invasion and growth of dangerous pathogens. On the other hand, disturbance and alterations in the gut microbiome—gut microbiota and their collective genes and genomes—are associated with a wide variety of diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, and asthma, and they may even play a role in autism spectrum disorders and neurodegenerative brain. disorders like Parkinson’s disease.

Many of the strong chemical ingredients in today’s cleaning products were put there specifically for their antimicrobial properties. The trouble with this strategy is that these chemicals aren’t selective—they kill probiotic organisms along with the types of bacteria we don’t want around. Some of these ingredients, such as parabens, ammonia, chlorine bleach, QUATS, Triclosan, and triclocarban, are absorbed through the skin in varying degrees—and once inside your body, they may upset your delicate microbial balance.

Triclosan is an antibacterial compound found in deodorants, antiperspirants, soaps, laundry detergents, toothpaste and hand sanitisers. Triclosan is also used as an ingredient to prevent bacteria, fungus, mildew and odours in other household products that are advertised as “anti-bacterial”. Triclosan can be absorbed through the skin and is currently believed to interfere with hormones, especially the thyroid, disrupting their normal functioning.

"We will all eat a peck of dirt before we die."

That was what our grandparents' generation used to say; a phrase which can be taken metaphorically to mean everyone will suffer some indignities and setbacks in their lifetime, but which is usually interpreted literally as meaning "Don't make a fuss about the bit of soil on your potatoes or the caterpillar on your lettuce - they're harmless"..and furthermore they seem to have some benefits too. Exposure to bacteria and viral organisms is critical to the development of a 'mature' immune system.

Cleaning it's good, disinfecting it's necessary sometimes. Same goes with medicine and antibiotics. Some time, we need them. But going overboard with any of them does more harm than good. As usual, I think that we have to choose our own battles and pick what works for us.

A drastic change it's usually not sustainable, nor enjoyable, but being a bit more aware of what we use and how it may affects us and taking conscious choice regarding it's a good starting point that may actually be very beneficial for us.

Sources:

댓글